Exhibits Events Past Program Highlights

|

Teaching Handwriting in America

from Colonial Times to the Computer Era

|

Not Your Grandmother's Cursive: Teaching Handwriting in America from Colonial Times to the Computer Era |

Rosetta Marantz Cohen, Professor of Education, Smith College |

Saturday, May 16th at 2 pm at Historic Northampton

|

|

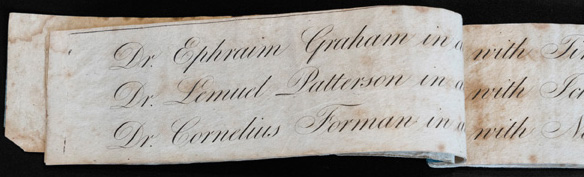

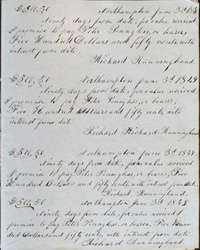

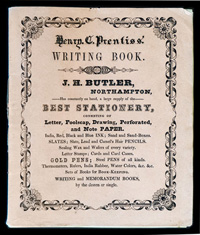

In 17th and 18th century America, there was a direct link perceived between handwriting and character. In his autobiography, Ben Franklin wrote that though he fell short of personal perfection, still “as those who aim at perfect writing by imitating engraved copies, though they never reach the wished for excellence of those copies, their hand is mended by the endeavor...” As the American economy began to grow, handwriting took on increasing importance. Increased letter-writing and the need for receipts, ledgers and materials associated with commercial activity meant that ordinary people needed to write well and to write in a way that inspired trust. |

Indeed, with the rise of printed material, handwriting took on more, not less symbolic meaning. While the printed page was devoid of character, handwriting presented the self to others. The first major figure in handwriting instruction in the United States was a New Yorker, Platt Rogers Spencer, whose Spencerian Method became a mainstay of education in post-antebellum America. Most schools during the period adopted the Spencerian Method which reduced the alphabet to a few elemental principles based in key forms found in nature: “the leaf, bud and flower, the wave-washed |

|

pebble, the shells that lie scattered on the floor.” Spencer highlighted the moral benefits of penmanship, and the self-discipline that good penmanship could impose. |

|

At the end of the 19th century, Spencer’s approach was replaced by the emergence of a rival pedagogy. Austen Norman Palmer’s Guide to Business Writing initiated an approach to writing instruction that seemed to fit with the modern age: muscular, un-embellished and fast. “What Americans need,” said Palmer, “is a plain rapid style adapted to the rush of modern business.” Palmer’s method stressed “unconscious habit” over conscious self-discipline-- physicality, power, and innate competence. Letters were composed of “pushes” and “pulls,” and students were required to sit and move their arms in a kind of calisthenics of the upper body. |

|

Today, controversies over how best to teach script have all but disappeared. The Common Core Standards call for the teaching of handwriting only in Kindergarten and first grade; after that emphasis is on proficiency on the keyboard. But neuroscientists tell us that there is evidence of links between handwriting and other forms of neural development: some studies show that students learn to read more quickly when they are taught to write first, but they are also better able to generate ideas and retain information. Others dispute this claim. There is good evidence on both sides. |

|

The talk is free and open to the public. |

This talk is held in conjunction with Letters from Away by Elizabeth Pol |

Contents Historic Northampton.