|

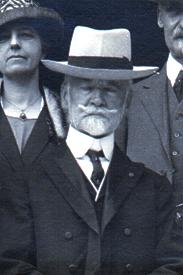

George Washington Cable

George Washington Cable (1844-1925) was well established in the literary world when he moved to Northampton in 1885. Born in New Orleans in 1844, Cable became a highly regarded novelist, noted for the realism of his portrayals of Creole life. The first of his stories of nineteenth-century New Orleans, Sieur George, appeared in the October 1873 issue of Scribner's Monthly. A second story, Belles Demoiselles Plantation, was published in the April 1874 issue. In 1879, Cable's collected stories were published as Old Creole Days. His first novel, The Grandissimes, was published in 1880 and in 1881, a novelette, Madame Delphine. In 1884, Cable published The Creoles of Louisiana and Dr. Sevier. Cable's writings introduced people to the history of New Orleans in the first three quarters of the nineteenth century.

Cable also advocated for social reform. While living in New Orleans, he wrote newspaper articles exposing corruption in the Louisiana State Lottery Company, served as superintendent of his church's mission school and advocated for prison reform. In September 1883, his prison reform efforts led to an invitation to deliver an address to the National Conference of Charities denouncing the convict labor system. The address was published in Century magazine in February 1884 in an article titled, "The Convict Labor System in the Southern States." In September 1884, he delivered an address at the annual meeting of the American Social Science Association of New York, "The Freedman's Case in Equity," published in January 1885, also in Century magazine. Cable's call for civil rights for African-Americans was denounced throughout the South, particularly by the newspaper press.

In summer 1884, Cable moved north tentatively with his family to Simsbury, Connecticut. Cable stated that the move north was primarily due to his wife's health, but his advocacy on the issue of race made him unwelcome in New Orleans. Some biographers have also suggested that his move north allowed better access to publishers, fellow authors and lecture audiences. Beginning in November 1884, Cable and Mark Twain toured 85 cities where they gave readings from their works. Cable wrote almost daily letters to his wife while touring with Twain. The letters were published in 1960 in Mark Twain and George W. Cable: The Record of a Literary Friendship by Cable biographer Arlin Turner, a professor of English at Duke University from 1953 to 1978.

On January 21, 1884, Cable gave a reading in Northampton at the invitation of bookseller, Sidney E. Bridgman. In late summer 1885, Cable left Simsbury to live in Northampton and with the help of Bridgman settled into a red brick house he called Red House at 61 Paradise Road in Northampton. Cable taught a bible class for adults at the Edwards Church. When attendance grew to nearly 100, the class was relocated to the Opera House and then to City Hall.

Arlin Turner writes that from 1885 to 1895, Cable wrote extensively on racial issues. In 1888, he formed the Open Letter Club, headquartered in New York and Nashville. Through the Open Letter Club, Cable aimed to gather prominent individuals to publicly discuss and publish views on racial issues. While the club disbanded in 1890, Cable himself published extensively on issues of racial equality. In 1958, Turner edited a collection of Cable's writings from this period titled The Negro Question: A Selection of Writings On Civil Rights in the South by George W. Cable. In his writings and lectures, Cable discussed a wide range of issues including the convict lease system, the right to vote, hold office and serve on juries, justice in the courts and intimidation by public officials, segregation or exclusion in transportation, schools and churches, conflicting assertions in the Constitution and Declaration of Independence, federal aid to schools and federal inervention to protect constitutional rights.

After one year of residence in Northampton, Cable established the Home Culture Clubs, which evolved over the next 22 years into The People's Institute.

In 1886-1887, a growing number of "small fireside clubs" were organized to meet in private homes "for unlaborious systematic reading." The Home Culture Clubs were created, Cable wrote, "for the educational and social culture of working men and women, the improvement of their home life and the establishment of friendly relations between widely separated elements of society." Groups met weekly from September to June; each club selected its topic of study. Study topics ranged from literature to American history to algebra to debate. Clubs reported activities weekly to the parent office, which distributed a weekly composite report. By 1889, there were 30 clubs with a membership of nearly 200. In June 1889, Cable announced plans to expand the clubs outside of Northampton. By 1894, there wer 54 clubs, 35 in Northampton, 10 elsewhere in Massachusetts and nine in other communities across the country. An 1896 advertisement for the clubs stated "their purpose is to combine the stimulations and pleasures of mutual improvement with the promotion of a kinder, fuller, and more active neighborliness than ordinarily results from merely drifting with the current of one's social preferences."

While visiting the clubs, Cable realized that many potential members did not have a suitable home in which to host meetings. In May 1888, two reading rooms were leased at 152 Main Street. The rooms were open from 6-10 p.m. in the evening. Within six months, the rooms featured 400 volumes as well as newspapers and magazines and served 600 readers per month.

In 1889, Cable hired Adelene Moffat to serve as the organization's first professional staff person. Cable had met Moffat, the daughter of temperance lecturer John Moffat, while speaking in Tennessee in 1887. Cable encouraged her to move north to study art and work as his personal secretary and assist him with the Open Letter Club. Philip Butcher, in his book, George W. Cable: the Northampton Years, writes that "it was Adelene Moffat who personified the Home Culture Clubs, both for the people who frequented the clubhouse and for many of the solid citizens whose contributions enabled to work to go on."

In 1893, a clubhouse in the former Methodist Church at 41 Center Street was acquired through the efforts of trustee Edward H. R. Lyman. The new headquarters provided the organization with meeting places for clubs and space for reading rooms, classes, lectures, concerts and social amusements for young people, including weekly dances. Adult education classed emerged as a main feature of the organization. Townspeople and Smith College students, generally juniors, were enlisted to teach. Class offerings were designed to meet the needs and interests of members and soon expanded to include a wide range of topics such as reading, arithmetic, astronomy, biology, bookkeeping, botany, cooking, dressmaking, literature, mechanics, German, French, geology and gymnastics.

Cable, Moffat and other staff members, including Mary and Anna Gertrude Brewster, published a monthly newsletter, the Letter, which described club programs, announced classes and included submissions by participants. In October 1896, it expanded into a literary magazine, The Symposium. Articles about the Home Culture Clubs appeared in newspapers such as the New York Tribune and in magazines such as Good Housekeeping, Outlook and Century magazine. In 1896, the Home Culture Clubs were incorporated as an educational and benevolent institution. Adelene Moffat was appointed general secretary-administrator of the organization. Cable served as president of the Board of Directors until 1920.

Cable relied on contributions from a small number of community members, particularly the Lyman family of Northampton. He also sought financial support from philanthropist Andrew Carnegie, whom Cable had met in 1883 as a result of his fame as an author. In 1903, Andrew Carnegie donated $50,000 towards the construction of a new building on Gothic Street, supplemented by community donations over five years. The building, known as Carnegie Hall, was dedicated on April 12, 1905 at a ceremony that brought Carnegie and his wife to Northampton. That year, a young lawyer named Calvin Coolidge joined the board, serving as secretary for 15 years. The following year the James House on Gothic Street was donated by Arthur Curtis James to house the household arts department.

In 1907, Adelene Moffat resigned over personal differences with Cable. Newspaper editorials praised her "earnestness, energy and genius in execution" as one of the clubs "chief mainstays and causes of success." In the reorganization that followed, Cable received annual operating support from Andrew Carnegie and raised $30,000 over the next ten years for an endowment. In 1909, the Home Culture Clubs became the People's Institute of Northampton because Cable believed the Home Culture Clubs had evolved into a "People's College."

In 1892, Cable moved from Red House on Paradise Road into a new home he called Tarryawhile - a Dutch colonial on a street newly laid out off of Paradise Road. As the first occupant on the new road, he named it "Dryads' Green" after Dryad Street in New Orleans. For the 1894 publication, Northampton: The Meadow City, Cable penned a description of the Paradise Woods area. The book's author noted that, "Mr. Cable is one of the most ardent lovers of the place. One or two scenes of his novel, John March, Southerner, are situated there, and being owner of a considerable portion of the tract, he has done much to beautify it." Cable landscaped the grounds, assisting with the gardening and designing the concrete foundations, garden-seats and tables for tea. He laid out contour path walkways in the woods towards the back of his property based upon the advice of his friend, George E. Waring. Bringing in a tree-lifter from California, a row of large white, red and post oaks were planted along the entire length of the street. Cable invited visiting friends to plant a souvenir tree on his property. Trees were planted by authors and celebrities of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries including James M. Barrie, Arthur Conan Doyle, Alice Freeman Palmer, Anna Hempstead Branch, Henry Ward Beecher as well as by local residents L. Clark Seelye, Gerald Stanley Lee and Jennette Lee. The Beecher Elm shown at right was first planted on the lawn of Red House and later moved to Dryads' Green.

In addition to gardening his property at Dryads' Green, Cable instituted a city-wide gardening competition in Northampton. In April 1898, Cable visited Andrew Carnegie at Skibo Castle in Scotland to seek funding for the Home Culture Clubs. There he learned of the garden competition that Carnegie sponsored at Dunfermline and returned with plans for a flower garden competition in Northampton sponsored by the Home Culture Clubs. Carnegie underwrote funding for cash prizes for the contest winners.

"In starting the competition," wrote Cable's daughter Lucy Leffingwell Cable Bikle, "my father, as president of the Home-Culture Clubs, personally visited hundreds of householders, explaining the project and urging them to join; and by the end of the first season some sixty gardens were well begun." Participants could not employ outside help or professional assistance. In the fourth year, 235 households participated. By 1913, nearly one thousand gardens were entered for 150 prizes determined by a council of judges. In 1914, Cable published the book, The Amateur Garden, in which he describes his "own acre" at Dryads' Green and the Northampton garden competition. The idea spread to Springfield, Massachusetts which began a similar garden competition.

George Washington Cable died in St. Petersburg, Florida on January 31, 1925. The buildings of the People's Institute were draped in mourning as Cable's body lay in state in Carnegie Hall until burial in the Bridge Street Cemetery. To this day, the People's Institute continues to serve the people of Northampton and surrounding communities. The records of the Home Culture Clubs and People's Institute are preserved at the Forbes Library in Northampton.

Contents Copyright 2025. Historic Northampton.