|

Native American Peoples II

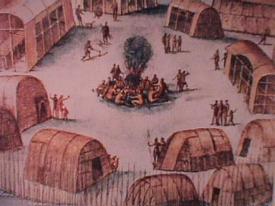

The primary social and political unit for Native Americans of Southern New England in the 17th century was the village, a kinship grouping of extended families rarely numbering more than 300 to 500. There were no formal "tribes," but cooperation among villages took place when circumstances demanded. Yet there was a series of interconnected homelands spread along the entire length of the Connecticut River Valley. The Native American settlement at what is now Northampton was called Norwottuck, or Nonotuck, meaning: "the midst of the river." It consisted of a core area where clan meetings and elders' councils were held. This area included communal cemeteries and probably sweat lodges used for curing. The meadows were planted with maize, beans and squash. Throughout the homeland area stood dozens of wigwams, sometimes in small hamlets. An extensive network of paths joined each clan's members and connected Norwottuck peoples to their kin who lived in nearby homelands centered around present-day Hadley, Deerfield and Northfield. The Norwottuck homeland also included several small, fortified areas, one of which was located on what is now called Fort Hill.

At first, European settlers and Native Americans reached a mutual accommodation. Initially, Europeans were dependent upon Native Americans for agricultural support. Indian maize was the lifeblood of early European settlement. Native Americans also controlled the supply of furs which dominated North American European trade. But as European settlements became more self-sufficient and the fur trade declined, Native Americans fell back upon the land itself as collateral for the exchange of goods.

Thus it was that on September 24, 1653, title to what became the European settlement of Northampton was conveyed to John Pynchon of Springfield by "Chickwallopp, Alias Wawhillowa, Neessahalant, Nassicohee, Riants, Paquahalant, Assellaquompas and Awonusk the wife of Wulluther all of Nanotuck" for the "consideration of one hundred fathum of Wampum by Tale and for Tenn Coates...."

As Europeans increasingly controlled access to the viable hunting, fishing and planting grounds, American Indians adapted as best they could. But it was an uneasy accommodation for all parties. In response to the growing permanent presence of the colonists in the valley, Indians negotiated agreements reserving to themselves long standing traditional rights. In this way they tried to remain connected to meeting places spoken of in their traditions, to places where the bones of their ancestors were buried, to places where they could continue to fish and plant corn.

Some native peoples chose to make themselves less visible by moving their wigwams beyond the fringes of colonial settlements. Less accessible settings such as ridgetops and small upland valleys now became home sites. In these newly occupied spaces, Native Americans could live without making their presence known - unless they wanted to. Intentional avoidance helped to ensure there would be Indian peoples in the valley long after 1700. However, their presence often went unrecorded.

In fact, Native Americans continued to live throughout the region, keeping alive their traditions while sometimes having to submerge their identities. Evidence reveals that Indian peoples continued to make a life for themselves. Plaited baskets, woven by Native Americans from carefully prepared and painted wood splints were prized items of exchange throughout the nineteenth century. Made for kitchen use, home storage or farm work, splint baskets represent some of the ways in which native and non-native peoples interacted from the eighteenth century onwards. As such, this basketry was part of a world in which native peoples continued their artistic traditions while also living as farmers, hired laborers, and artisans in non-traditional communities.

Contents Historic Northampton.